Alright, I am going to briefly bring this thread back from the dead to do my yearly check-in.

That being said, I occasionally get a batch of plates that are insanely bright with a nice dynamic range using air-gelatin only. I just don't know what I did, so I can't make them consistently like that!

In 2019 I made a single batch of plates using air-gelatin reflection only, that had incredible brightness, saturation and dynamic range. I only shot maybe a quarter of those plates, having figured "oh hey I guess I've got this process more or less figured out", and focused my time on autochrome experiments. The plates sat for a few months and eventually went bad (bright silver deposits anytime they were developed, kind of like looking at very old b&w prints that weren't stored very well), and any time I tried reproducing that batch, I could only manage not-so-great results. This year I shifted primary focus to see if I could figure out what I did then, and started to

absolutely lose my mind. I have one or two plates from my "magic" 2019 batch that I jealously hold onto now to anchor me to my sanity.

I could not reproduce my 2019 results with the standard "Darran Green's" recipe, despite running the same one over and over quite a few times. I started to tweak different aspects of it, trying to retrace my steps and figure out if I accidentally did something "wrong" and deviated from the recipe, inadvertently producing better results. I don't think I'm quite at that level yet, but I have learned quite a few things even compared to a few months ago.

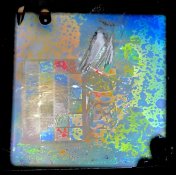

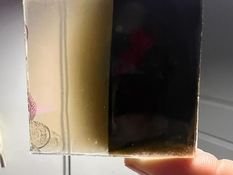

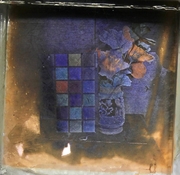

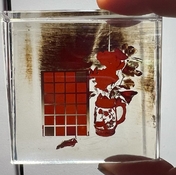

Here is one of the better examples of my magic batch, and is my end goal for what I'm trying to reproduce with this process. It's a bit blueshifted, but finer details can be easily seen, and the white flower is notably not solarized.

It's not easily visible here, especially now with the back of the plate painted black, but of particular note is that the edges of the plate and shadow areas that receive the least amount of light are

crystal clear. In my many follow ups, shadow areas were often full of thick silver deposits that still produce a good blacks, with overall good results on the rest of the colors. However, I think the very best examples of Lippmann plates that can be made with the air-gelatin method will probably lack these thicker silver deposits. We'll touch more on this later.

1. The Standard Green Recipe

My goto version of the Lippmann emulsion recipe can be found on Page 13 of "The True Colour of Photography" by Hans Bjelkhagen and Darran Green, document attached to this post. I won't fully write out all the details of the process, but I want to touch on a few things it does here.

1. Heat up 4g gelatin in 100mL of water, until the gelatin has melted (I usually do 40C).

2. Decant 20mL of the gelatin solution to a second beaker.

3. In the 20mL portion, add 680mg KBr and 48mg KI (I use a 1% solution of KI here, so 4.8mL of that)

4. In the 80mL portion, dissolve 1g AgNO3.

5. When the solution has cooled to 35C, add in the halide salt solution to the AgNO3 solution with a syringe over a minute or so.

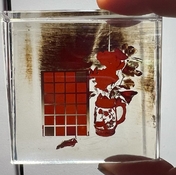

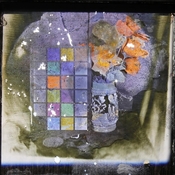

I ran this recipe many times, but I could not shake off the fact that it was producing extremely high contrast results, with an inability to render more subtle colors. Results typically looked something like this:

For my GP-2, I keep the ammonium thiocyanate in a separate 3% solution. Typically development here is about 7.5mL GP-2 "stock" + 2mL ammonium thiocyanate (3%) + 100mL water, for 4 minutes or so.

I played around with different exposures, development times, ammonium thiocyanate concentrations in GP-2, different pyro developers, filtration, spectral dye concentrations, you name it - but I could not shake the insanely high contrast of these plates, while at the same time even approaching the level of brightness and saturation that I previously got.

Of note, anyone familiar with more standard silver-gelatin emulsions will see that the AgNO3 and halide salt solutions are swapped - typically you add the silver to the halide solution, but it's the other way around in this recipe. Green did this because, even though the halide salts are overall in stoichiometric excess, most of the addition occurs in a solution with an excess of AgNO3. This is used to keep the crystal sizes from growing too large.

2. My "Blue Period" - Halation

I noticed that when I was running these emulsions and precipitating at 35C, they often inevitably had a strong blue tone to them, and it took me a real long time to shake it. I had some good results, but they were the exception, not the rule.

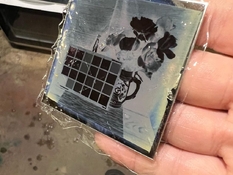

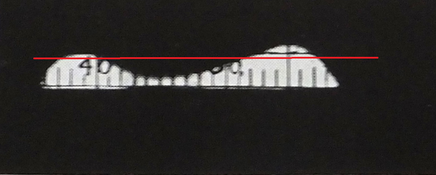

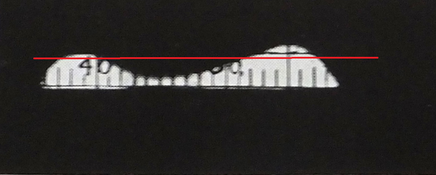

The flowers had a strange red halo around them, in an otherwise overwhelmingly blue image. Yellow filtration did not help cut the blues down, the images remained blue, but actual blue objects in the shot would lose brightness and disappear. Shadow areas were often muddy and indistinct, and I eventually started to wonder if there was just an insane amount of halation happening during exposure. I ran a test by covering half the plate with black construction paper.

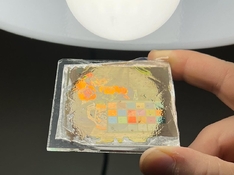

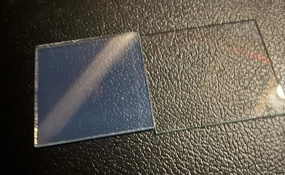

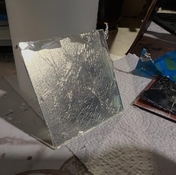

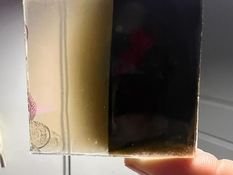

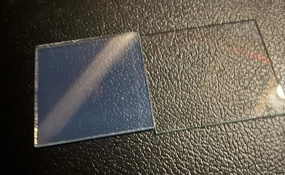

Yup, we're getting some insane halation here. Here's how one of the unexposed plates looked in the light compared to a piece of glass.

Yup, that's gonna be no good.

I eventually resolved the issue by realizing

I wasn't even running the "standard" recipe correctly to being with. Here's what I was doing:

A: 4g gelatin, 1g AgNO3, 100mL water

B: 680mg KBr, 4.8mL 1% KI, 80 mL water

B into A at 35C

The halide solution had no gelatin in it like the recipe called for. When I readjusted to be more in line with the standard recipe, the blue tones mostly went away, though the shadow areas still had thick deposits of silver.

3. Lower Precipitation Temp

I eventually figured out that crystal clear plates could be obtained every single time by lowering the temperature at which precipitation happens. At 35C, it was often a toss up as to whether the plates would still be somewhat milky or not, but by precipitating at 30C or lower, shadow areas have always been consistently clear. I haven't noticed much of a difference in performance once you're below 30C, but these days I do it anywhere from 26C-28C.

This didn't do much for my contrast issues, the chart and flowers still stubbornly are floating in a black void, but now the plates are starting to look a lot more like my 2019 batch, at least when looking through them.

4. 2x, X into Ag

When experimenting with thin coatings, at one point I found that by diluting the emulsion with a gelatin solution, the gelatin-diluted plates were extremely dim, compared to emulsions only diluted by water. This make sense - the fringe pattern for white light is extremely shallow, and diluting the emulsion 1:1 with a gelatin solution more or less displaces 50% of the AgX from that shallow area. Taking this knowledge, I tried to apply it in the opposite direction - what would happen if we double everything in the recipe

except the gelatin? If we keep the dilutions of all the ingredients the same relative to each other except the gelatin, we should be able to cram twice as much AgX into that shallow area, and hopefully produce brighter, faster plates.

The new recipe for this is:

1. Heat up 4g gelatin in 180mL water to 40C until it melts

2. Decant 40mL of the gelatin solution

3. Add 2g AgNO3 to the 140mL portion of gelatin

4. Add 1360mg KBr, 9.8mL 1% KI to the 40mL portion

5. At 28C, add the halide salts into the silver salts. 500RPM magnetic stirring. Addition usually about 1m15s.

The more observant readers here will notice that I'm starting to take more detailed notes, inversely proportional to the amount of hair I have left on my head, due to this process making me want to tear it all out.

This did not help at all with my contrast or speed, but it did produce some very nice plates. Of note, the plates were very bright and very saturated. These "2x" emulsion formulations needed to have the GP-2 slightly modified by backing the ammonium thiocyanate concentration off a bit, perhaps due to the higher availability of silver ions in the emulsion. Normal development for these was 15mL GP-2 "stock" + 2mL 3% ammonium thiocyanate + 100mL water for about 2 minutes.

The results were interesting and temporarily pleasing, but I knew I could do better. Flower subjects worked pretty well, but all the subtle colors were still getting blown out of existence. I have a theory about that...

Here's highly technical diagram.

I have to wonder if, due to the extremely high contrast nature of the emulsion, the wavelengths that fall within a narrow area of the peaks in sensitivity, just become massively overrepresented in the final image by the time the plate has "exposed" and the wavelengths that fall outside of these areas don't really even get a chance to have much action on the plate.

I've hit the image attachment limit, so this post will be continued in the next one.