Hmmm! This statement must be said with a wink. A few years back I took a picture of a locomotive with all it's brass knobs, shiny chrome and deep blacks. Nice bright sunny day with plenty of clouds. I was using an old Kodak Monitor 620 with red "special" lens and respooled 120 PanF+. Shooting with the sun behind me and using my meter in incident mode, I bracket 1 stop each side in 1/2 stop increments. I then developed the roll in Rodinal 1:100 for 30 minutes, stand. Actually, I think it was more like 40 minutes, but can't remember for sure. I had no complaints except for a hardly noticeable bit bromide drag. The clouds were just as detailed as I remember, shadows very good, as were the blacks. Even the white limestone between the track ties held perfect detail. Like I said, I had no complaints and I'm sure I could have figured out how to take care of the bromide drag problem. I found the frame taken at ISO 32 equivalent was the best. I never went further in testing or using PanF since I preferred fast film (HP5+) when shooting 120 format. I don't shoot 35mm very much at all, but if I did I would certainly try to see what I could do with PanF and my Contax G-lenses. It might not work stand development wise with all those sprocket holes and bromide drag. Of course, one doesn't know until one tries. JWIts a great film and it could build up contrast really fast. So you may tune your dev. times for contrast and exposure to capture shadow detail.

* Do not stand develop this film in Rodinal @1+100

-

Welcome to Photrio!Registration is fast and free. Join today to unlock search, see fewer ads, and access all forum features.Click here to sign up

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

What is your experience with Pan F 50 Plus?

-

A

- Thread starter ColdEye

- Start date

Recent Classifieds

-

Want to Buy Nikon F2 black camera

- Started by ediz7531

-

Want to Buy Sekonic l-308 lumisphere

- Started by jwd722

-

For Sale Vacuseal Vacuum Press 4468H

- Started by oficinouno

-

For Sale Paper Safes and glossy photo paper

- Started by oficinouno

-

For Sale Nikon d810, RRS bracket, battery charger and 3 batteries..$800

- Started by ChrisK

Forum statistics

baachitraka

Member

Update:

* Do not stand develop this film in Rodinal @1+100 for an hour

In 35mm I have witnessed very ugly effects of drag around sprocket holes.

I shot three PanF+ in 35mm in Florence on a bright and sunny, so I was naturally looking to tame the contrast a bit (not really necessary but my head was rendering a different negative given the nature of the film etc.,..).

Luckily I developed one role at once, so I can save other two.

* Do not stand develop this film in Rodinal @1+100 for an hour

In 35mm I have witnessed very ugly effects of drag around sprocket holes.

I shot three PanF+ in 35mm in Florence on a bright and sunny, so I was naturally looking to tame the contrast a bit (not really necessary but my head was rendering a different negative given the nature of the film etc.,..).

Luckily I developed one role at once, so I can save other two.

Last edited:

JensH

Member

Hi,

looks fine. And the 356 B, too.

I like to see and hear them on the road.

Best

Jens

It is a wonderful film. It is contrasty and slow. You should use it in situations that use these features to advantage. Cloudy bright days, camera mounted on a tripod.

Ended up at the zoo instead, I set my F3 at ISO 50, no compensation and at Auto. Followed the developing times for HC 110 Dil B. I like it, contrast is high so I might experiment with my developing. DSLR scans inverted in VueScan, pardon the dust. i really wish I could print these. Hopefully before the year ends I can set up a guerrilla darkroom.

- Joined

- Jul 14, 2011

- Messages

- 15,008

- Format

- 8x10 Format

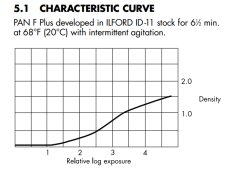

The characteristic curve explains it all. It's basically an S-curve with very little straight line. So this is a very poor choice of film for high contrast situations. But if the lighting is softer, it can work magic. The poor latent image keeping qualities are well documented. I wouldn't worry about developing it a month later, but six months or a year later might bring you irremediable issues. I rate it at 25 and develop it in 5:5:100 PMK pyro for only 6 or 7 min @ 68F. It does streak more easily than other films, so a tiny amt of EDTA in the dev solution helps.

- Joined

- Jul 26, 2009

- Messages

- 4,307

- Format

- 35mm

I’m wondering.

Could we use this film and if we were to be unsatisfied, by the end of the day, could we just leave it undeveloped for let’s say 5 years so the images could get completely erased? And then reshoot it?

No? If the answer is no, this proves a few points. The first point in no particular order, would be that the silver doesn’t regenerate itself. Also, another point is that it doesn’t start degenerating as soon as it’s exposed, but rather as soon as the film has been manufactured. It basically starts to expire as soon as it’s manufactured.

There is really a point to be made wether Ilford sells this film unfresh. And they very well could, because slow film doesn’t fog as it ages, but it can have a side effect of losing sensitivity as all films do. Therefore people simply underexpose it as they shoot and they mistake it as “poor latency”.

I’m amazed at the fact that my own experience of excellent Pan-F image latency is ignored while everyone favors the theory of poor latency just because they read it somewhere. And of course, the internet has this way of spreading truths *Yawn*

I’ve simply not encountered this problem. Therefore I just can’t accept it as universally true. I’m much more inclined towards my theory of it being expired and therefore underexposed at iso 50, depending on which production roll you are using. It is a much more plausible theory.

And I really doubt that this film is a great seller. They manufacture it once and restart production when it dries up, which according to the internet “truths”, it is what happened to the original acros; so many people had these theories flying around. Well now this might well be pan-F’s truth as well. I’ve yet to read a scientific explanation on pan-f, it’s all parroting.

Could we use this film and if we were to be unsatisfied, by the end of the day, could we just leave it undeveloped for let’s say 5 years so the images could get completely erased? And then reshoot it?

No? If the answer is no, this proves a few points. The first point in no particular order, would be that the silver doesn’t regenerate itself. Also, another point is that it doesn’t start degenerating as soon as it’s exposed, but rather as soon as the film has been manufactured. It basically starts to expire as soon as it’s manufactured.

There is really a point to be made wether Ilford sells this film unfresh. And they very well could, because slow film doesn’t fog as it ages, but it can have a side effect of losing sensitivity as all films do. Therefore people simply underexpose it as they shoot and they mistake it as “poor latency”.

I’m amazed at the fact that my own experience of excellent Pan-F image latency is ignored while everyone favors the theory of poor latency just because they read it somewhere. And of course, the internet has this way of spreading truths *Yawn*

I’ve simply not encountered this problem. Therefore I just can’t accept it as universally true. I’m much more inclined towards my theory of it being expired and therefore underexposed at iso 50, depending on which production roll you are using. It is a much more plausible theory.

And I really doubt that this film is a great seller. They manufacture it once and restart production when it dries up, which according to the internet “truths”, it is what happened to the original acros; so many people had these theories flying around. Well now this might well be pan-F’s truth as well. I’ve yet to read a scientific explanation on pan-f, it’s all parroting.

Last edited:

I’m wondering.

Could we use this film and if we were to be unsatisfied, by the end of the day, could we just leave it undeveloped for let’s say 5 years so the images could get completely erased? And then reshoot it?

No? If the answer is no, this proves a few points. The first point in no particular order, would be that the silver doesn’t regenerate itself. Also, another point is that it doesn’t start degenerating as soon as it’s exposed, but rather as soon as the film has been manufactured. It basically starts to expire as soon as it’s manufactured.

There is really a point to be made wether Ilford sells this film unfresh. And they very well could, because slow film doesn’t fog as it ages, but it can have a side effect of losing sensitivity as all films do. Therefore people simply underexpose it as they shoot and they mistake it as “poor latency”.

I’m amazed at the fact that my own experience of excellent Pan-F image latency is ignored while everyone favors the theory of poor latency just because they read it somewhere. And of course, the internet has this way of spreading truths *Yawn*

I’ve simply not encountered this problem. Therefore I just can’t accept it as universally true. I’m much more inclined towards my theory of it being expired and therefore underexposed at iso 50, depending on which production roll you are using. It is a much more plausible theory.

And I really doubt that this film is a great seller. They manufacture it once and restart production when it dries up, which according to the internet “truths”, it is what happened to the original acros; so many people had these theories flying around. Well now this might well be pan-F’s truth as well. I’ve yet to read a scientific explanation on pan-f, it’s all parroting.

to be fair, there’s no telling when it was actually manufactured, and I can attest that it is a very slow selling film, so it wouldn’t surprise me in the least if Ilford only did one manufacturing run every year or two.

that being said, the edge markings do fade faster than other films. I have a number of rolls that I’ve barely had for a year and the expire in late 2021 and the edge markings are barely visible.

- Joined

- Jul 14, 2011

- Messages

- 15,008

- Format

- 8x10 Format

Master rolls are probably kept in cold storage anyway. I have zero reason to think the film itself is likely to be pre-degraded, nor did I just "read somewhere" that the latent image stability is less than ideal. I've experienced it, specifically with rolls dev too late from the very same batch and even pk as rolls which otherwise dev perfectly. Since NB23 makes ridiculous statements about ACROS, I suspect he's shooting from the hip about PanF too.

Last edited:

craigclu

Subscriber

I had a large amount of PanF+ over 10 years old (frozen) and did a controlled test of the oldest in the freezer vs freshly purchased, current emulsions. The curves laid perfectly over each other, giving me confidence that the older film would perform as the new film did. This doesn't speak to the latent image issue but indicated to me that the emulsion was stable, at least when carefully stored. I don't recall now about the edge markings (it was long ago that I did this).

- Joined

- Jul 26, 2009

- Messages

- 4,307

- Format

- 35mm

Playing the devil’s advocate, for the fun of it:

-Given the fact that film ages and deteriorates, how can you be sure that your old film wasn’t from the same batch as the new, fresh film?

-Given the fact that film ages and deteriorates, how can you be sure that your old film wasn’t from the same batch as the new, fresh film?

I had a large amount of PanF+ over 10 years old (frozen) and did a controlled test of the oldest in the freezer vs freshly purchased, current emulsions. The curves laid perfectly over each other, giving me confidence that the older film would perform as the new film did. This doesn't speak to the latent image issue but indicated to me that the emulsion was stable, at least when carefully stored. I don't recall now about the edge markings (it was long ago that I did this).

The characteristic curve explains it all. It's basically an S-curve with very little straight line. So this is a very poor choice of film for high contrast situations. But if the lighting is softer, it can work magic. The poor latent image keeping qualities are well documented. I wouldn't worry about developing it a month later, but six months or a year later might bring you irremediable issues. I rate it at 25 and develop it in 5:5:100 PMK pyro for only 6 or 7 min @ 68F. It does streak more easily than other films, so a tiny amt of EDTA in the dev solution helps.

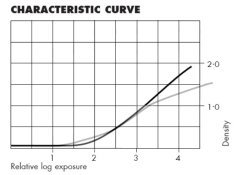

See Ilford's published curve for Pan F and FP4. FP4's is S-shaped, while Pan F has a longish toe and the rest of the curve is straight.

Here's what it looks like in replenished XTOL: https://www.photrio.com/forum/resou...lenished-xtol-for-15-00-at-24c-in-a-jobo.424/

I like it a lot, especially when I'm seeking a little more contrast in light that's a little flat. My ancient rolls in the freezer are fine, a lot better than ancient rolls of faster film in the freezer. I like it in Xtol, at Ilford's recommended speed and development time. Rodinal looks great at 1:25 if the lighting was flat.

- Joined

- Jul 14, 2011

- Messages

- 15,008

- Format

- 8x10 Format

mmerig - you're totally wrong. Look at the length of the published curves in relation to each other. Practical testing confirms exactly what I stated, and it's been a known problem with PanF for decades. Even Ilford's marketing literature and description of these two respective films implies exactly the same thing. I've made hundreds of densitometer plots with FP4 (both old and new style), have shot and printed a great deal of it, especially 4x5 and 8x10 sheets, and have every legitimate reason to believe I understand these films far better than you do. I've got the two published curves right in front of me, right now, in their official tech sheets. You've stated all this backwards. It's Pan F that has the limitations of an S-curve, and FP4 the long straight line once it launches off the toe.

Last edited:

mmerig - you're totally wrong. Look at the length of the published curves in relation to each other. Practical testing confirms exactly what I stated, and it's been a known problem with PanF for decades. Even Ilford's marketing literature and description of these two respective films implies exactly the same thing. I've made hundreds of densitometer plots with FP4 (both old and new style), have shot and printed a great deal of it, especially 4x5 and 8x10 sheets, and have every legitimate reason to believe I understand these films far better than you do. I've got the two published curves right in front of me, right now, in their official tech sheets. You've stated all this backwards. It's Pan F that has the limitations of an S-curve, and FP4 the long straight line once it launches off the toe.

which data sheets are you looking at? I just went to Ilford’s website and pulled both down. Panf is straight, Fp4 is S shaped.

which data sheets are you looking at? I just went to Ilford’s website and pulled both down. Panf is straight, Fp4 is S shaped.

This is Pan-F in ID-11 stock from the late 90's data sheet, and then the same curve resized to match the Ilfotech HC curve in the current data sheet and super-imposed - black is HC, grey is ID-11. Stick a line of best fit on the HC curve and you'll see that there are the distinguishable beginnings of a shoulder. Not hard to see how the seemingly weird curve form in ID-11 can confuse people - lower shadow/ highlight contrast and relatively normal midrange contrast - which does make sense from a design perspective for dealing with bright/ contrasty conditions. I have to say that that curve form more closely delineates my own experience with Pan-F rather than my earlier comments about it having apparently had a design intent to match with transparency films (which I recall may have been in some Ilford official communique/ interview I found - but I may have been confusing it with something reversal process related).

Attachments

Last edited:

- Joined

- Jul 14, 2011

- Messages

- 15,008

- Format

- 8x10 Format

Pan F does work best if you target for subject contrast range similar to what works well for color slide film. Otherwise the long toe of the S curve equates to very bland shadow gradation, and the rapid shoulder blows out any highlight texture. It's an obvious characteristic in practice. Neither Pan F plus nor FP4 plus have changed, so neither have their characteristic curves relative to specific developers changed. The latest tech sheets they've posted are dated Nov 2018. I'd contact them. Something indeed looks fishy, even impossible, and a complete mismatch to their own longstanding descriptions of ideal applications for these respective films. I think somebody got diagrams accidentally switched. FP4 has a distinctly shorter toe than HP5, and can be developed for a very long straight line thereafter, and does not produce an S-curve at all. By comparison, Pan F would be an almost worthless film for copy work, color separations, and wide exposure range - the very features FP4 is commended for in the tech sheet itself. So I 100% stand by my own previous comments. If somebody wants to dispute that, do some basic densitometer work of your own. I've certainly paid my dues in that department. Otherwise, learn the hard way, and try using PanF for the same kind of relatively high contrast situations where everyone knows FP4 competently works - no, not quite as well as TMax films, but a helluva lot better than PanF or even HP5.

Last edited:

At this point I am too afraid to ask what all these terms like "S Curve" and "long toe" mean lol

- Joined

- Jul 14, 2011

- Messages

- 15,008

- Format

- 8x10 Format

Get a tutorial on basic Sensitometry. Different kinds of films are engineered for potentially different ideal applications. Besides format sizes, exposure speed, granularity, spectral sensitivity, etc, each has what's called a "characteristic curve" which determines how any particular film distributes the light it receives in terms of negative density from low low to high. That's why such curves are routinely published in the tech sheets. These curves can be altered somewhat by the specific type and degree of development; but curves which are widely different in general will produce quite different results trying to handle the same scene contrast. For example, a few times I've carried 120 Pan F into the mountains. The results were lovely and silvery across the board from low contrast scenes in rain, mist, and falling snow. But in open sun high contrast situations the results were very disappointing, because the shadows were all empty and blaah, and the highlights were blown out. The characteristic S-shaped curve of this film just can't handle high contrast. By comparison, a film like FP4 or Acros would do far better, and a film with a very long straight line and short toe like TMax, better still, but in return demands more careful shadow metering. Here on the coast, Pan F can give lovely results during our "natural softbox" conditions when the fog is in, but be quite disappointing when the fog lifts if there is a substantial amount of shadow content in the scene. Our deep redwood forests, for example, can impose an extreme 12 stop range of contrast in open sun conditions, which few films handle well. But Pan F has a wonderful signature of "wire sharpness" that attracts some people to it. Since it's not made in large format sheets, I don't use this film very often, but it's a great option for certain things, and I do shoot it in 120 from time to time.

Last edited:

baachitraka

Member

At this point I am too afraid to ask what all these terms like "S Curve" and "long toe" mean lol

Parallel world in the world of photography

Terminology may be new to some, but I think anyone who's ever used "Curves" tool in any image editing program would immediately understand the meaning of this.

Maybe I'm taking this off-topic, but do densitometers still make sense? Modern camera sensors pack so much dynamic range at their native ISO. Is it possible to produce the characteristic curve of a film by stacking 11 grey cards for each zone to fill 100% of the frame, shoot RAW exposing for the middle, convert to TIFF using linear curve and then sample luminosity in each zone? What does the old school method of shooting 11 exposures with the same card, and using densitometer add to the table?

Maybe I'm taking this off-topic, but do densitometers still make sense? Modern camera sensors pack so much dynamic range at their native ISO. Is it possible to produce the characteristic curve of a film by stacking 11 grey cards for each zone to fill 100% of the frame, shoot RAW exposing for the middle, convert to TIFF using linear curve and then sample luminosity in each zone? What does the old school method of shooting 11 exposures with the same card, and using densitometer add to the table?

Terminology may be new to some, but I think anyone who's ever used "Curves" tool in any image editing program would immediately understand the meaning of this.

Maybe I'm taking this off-topic, but do densitometers still make sense? Modern camera sensors pack so much dynamic range at their native ISO. Is it possible to produce the characteristic curve of a film by stacking 11 grey cards for each zone to fill 100% of the frame, shoot RAW exposing for the middle, convert to TIFF using linear curve and then sample luminosity in each zone? What does the old school method of shooting 11 exposures with the same card, and using densitometer add to the table?

A densitometer and a step wedge (and if you really want, a sensitometer) does it all in one shot. There are ways around the densitometer if needed. Much simpler (but in the past, much costlier) than the grey card methods - and the grey cards also introduce the variable of flare into the imaging system, which while significant to a specific camera/ enlarger/ scanner, may distort your overall results.

| Photrio.com contains affiliate links to products. We may receive a commission for purchases made through these links. To read our full affiliate disclosure statement please click Here. |

PHOTRIO PARTNERS EQUALLY FUNDING OUR COMMUNITY:  |