Just a couple of thoughts about exposure. When it comes to the perception of quality, we can all agree that there arent any absolute hard and fast boundaries. Part of what is considered quality depends on intended use. Large format landscape photographers usually require higher standards of quality, but there is an entire field of photography that routinely over rates the film and uses push processing. There are many extraordinary examples of photojournalism that would have been exposed at what is considered just acceptable which falls under the 0.3G point.

One thing we need to remember is that the 0.3G point is not the minimum gradient which will produce an excellent print. It is the minimum shadow gradient based on the overall average contrast. A scene with a long luminance range requires reduced development in order to print on a normal grade of paper, but as long as the shadow is above a gradient of 0.3x the average, the print will still be considered excellent. That means as the overall gradient changes, there is a shift in the viewers perception of quality as it relates to the requirements of the shadows. An acceptable shadow gradient for a long luminance ranged subject would look flat for a normal range.

Just because it is the minimum gradient for a given degree of processing, doesnt mean that it is the aim gradient for the exposure or that it shouldn't be increased. Studies show that quality is maintained with additional exposure beyond 0.3G which consequently produce higher shadow gradients. The amount of additional exposure as it relates to quality is mostly limited by the degree of intended enlargement as grain and sharpness will then become factors.

As Ron points out, modern films have a very long straight-line portion and very little toe. His recommended +1/3 stop exposure or Ralphs +1/2 stop exposure will place the exposure on or mostly on the straight-line portion. This will give the maximum possible shadow separation for that emulsion. Additional exposure beyond placing the shadow at the beginning of the straight-line portion is unnecessary as it wouldnt produce any additional increase in the shadow gradient.

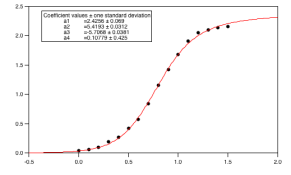

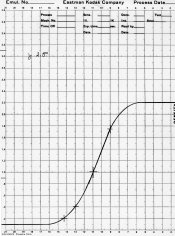

However, long toe films are still being made and as we can see from the example Ron posted earlier (which I consider to have a long toe), the required additional exposure necessary to place the shadows on the straight-line portion (point A in the example) is considerably more than what would be required for a short toe film. Any equal amount of exposure would yield different and therefore inconsistent levels of improvement in the shadow gradient depending on the film type used. In Rons posted example, the required exposure to place the shadows on point A would be around three stops higher than the 0.3G speed point and around two stops higher than the current ISO speed. It would be necessary for the long toe film having the same ISO speed and same CI as a short toe film to have an effective two stop lower EI in order to place the shadows on the straight-line portion and produce an equal amount of shadow separation as the short toe films straight-line portion.

Im thinking that since long toe films are still being made in a time when the technology makes possible for very short toe films, there has to be a reason. Why buy a long toe film just to have to give it substantially more exposure in order to move the exposure off the toe? Maybe long toe films arent as strictly subject to the concept of placing all the exposure on the straight-line portion of the curve?

The perception of quality is relative after all. The eye tends to compress the lower values anyway. You only need to look at an equally spaced gray scale to confirm it. Munsells scale has equally visually spaced steps. There is greater separation in the shadows in order to make it look equally spaced. Now this is a good argument for using the maximum gradient possible. I agree, but it can also suggest that as we are used to seeing flatter shadow detail in nature it will accept it in a print to a degree. As a side note I contend that only with comparisons of the same scene shot with a long toe and short toe film will a person be able to see the differences produced by the curve shape. Generally the subject matter and the fact that our perception is relative will tend to obscure any tonal reproduction differences based on curve shape. Its like relative pitch.

It is probably safe to assume that there is unanimous agreement here that good shadow contrast is critical in producing an optimum looking reproduction. There will, of course, be disagreements as to the degree. As gradient is the key factor in the perception of quality, we must then conclude a fundamental problem exists with any system of speed / exposure determination that uses a point of density without taking into account the surrounding local gradient. The Zone System is an obvious example of only using a fixed density point. Without taking the local gradient into account, simply applying a fixed amount of exposure or additional exposure above any standardized speed rating will produce less than consistent results depending on the shape of the film curve. This isnt important if a photographer limits themselves to a single film type, but becomes more of a concern with multiple film types or if it is applied as a systematic rule to all film types.