As a complete beginner, it looked "easy" on paper.

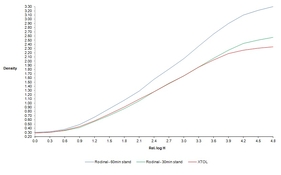

But normal agitation is just as easy, takes less time and involves less risk of uneven development. The alleged self-compensating nature of stand development is IMO often overstated. This self-compensation is why it's supposed to work - shadows would be allowed to continue to develop as developer exhausts in the highlights. In practice, this only works to an extent, and under certain conditions. It requires that the developer is balanced on the brink of exhaustion to begin with, which is why this is done with very dilute developers like rodinal or pyrocat, and it doesn't work at all with developers like XTOL or D76. Even so, the developer will have to be diluted to just the right amount to make the most of this compensating effect and that's a bit of a hit & miss endeavor. Self-compensation also relies on an absolute lack of mobility of developer through the emulsion, which should prevent fresh developer to be supplied to highlight areas that must hold themselves back. However, in free-standing watery liquid at room temperature, mobility is far from zero and there will actually be a significant amount of 'self-agitation' and diffusion through the emulsion.

Theoretically, stand developmnet should keep highlights in check even if you extend the development time significantly. In practice, this isn't the case and highlights do actually block up. As you've found out, there's no standard recipe for stand development. Films respond differently w.r.t. the rate of development. You'd have to adjust the dilution and time for stand development to match the film.

As

@Andrew O'Neill says above, the main drawbacks of stand development are unevenness. This manifests in several ways; especially on sheet film, mottling can be a problem. Bromide drag tends to manifest on 35mm in particular due to the sprocket holes, although I believe that 99% of the 'bromide drag' cases are in fact instances of surge marks that result from differences in flow patterns (see remarks on auto-agitation above). The reason I believe this is that the sprocket holes tend to leave 'trailers' across the film and these are alleged to be bromide drag trails - but the sprocket hole areas of 35mm film typically do not (or barely) release any bromide during development, so that theory doesn't really hold. However, the sprocket holes do affect how liquid moves across the film and this can create differences in the rate of supply of fresh developer (through inherent motion of the liquid even without external agitation) to the film. Extending this thought, you often see uneven development patterns along edges of sheets or rolls of film with stand development routines, and this unevenness often correlates to geometry of the tank, reels (and e.g. in 35mm film, the film itself). I've run into this myself when using a Mod54 holder for 4x5, where the 'fingers' of the holder created surge markes that extended into the image area on 4x5" sheets.

Overall, there's IMO no good case to be made for stand development. There can be merit to reduced agitation, which can be done to different degrees - e.g. a long development time of something like 45 minutes with 2 or 3 bouts of agitation at 10-15 minute intervals, or a somewhat shorter development time (12-20 minutes or so) with agitation intervals at 3 minutes. What this achieves is some compression, but more importantly (IMO) increased edge effects that enhance contrasty edges in the image and thus affect the apparent sharpness of the images. This result can be very subtle (difficult to distinguish at all) or sometimes very extreme (I've had cases where it was just way too much) and it can be difficult to control.

If you're just starting out, the best advice I can give you is to just stick to the normal agitation procedures that have been tried and tested for well over a century and that will give good, consistent results, every time.

.... Since I developed that roll I moved to a different state and I haven't been able to find the box that contains the film I developed before the move.

.... Since I developed that roll I moved to a different state and I haven't been able to find the box that contains the film I developed before the move.