falotico

Member

- Joined

- Aug 31, 2012

- Messages

- 265

- Format

- 35mm

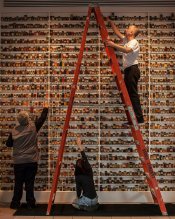

Mark Osterman on his Facebook page posted a photo of a display at Eastman House for the exhibit, "In Glorious Technicolor". http://eastman.org/technicolor/glorious-technicolor It shows the museum docents setting up a wall of various bottles containing dyes that were once part of a collection of the Technicolor Company. In addition to the exhibit, a book "The Dawn of Technicolor, 1915-1935" by Layton and Pierce has been published. Holmburgers sent out an email to members of the Dye Transfer group which recommended this book. I had an early order and my copy came this week. It promises to be one of the fundamental books on Technicolor Dye Transfer. The others include Cornwell-Clyne's "Colour Cinematography" and Richard W. Haines, "Technicolor Movies, The History of Dye Transfer Printing" which is available on Google Books.

"The Dawn of Technicolor" is a thorough account of the beginnings of the company and the films it made using the earliest processes up until the first full color camera. It deals minutely with business decisions and provides clear biographical details of the people involved at the center of the firm. These are some of the most important names in the history of color photography: Kalmus, E.J. Wall, Comstock, Troland et al. The editors provide beautiful color reproductions of frames and images from all of the major films in the period they discuss; to which they add a complete filmography which lists all of the holdings for these films in principal institutions worldwide. The book however does shy away from specific technical descriptions. It only mentions two specific dyes; does not describe mordants, formulas, temperature or timing. For this information you must look to Cornwell-Clyne or relevant patents.

Out here in greater Los Angeles where movies are a religion I go to a collectors' group where vintage film prints are shown. A couple of months ago one of the collectors brought in a magazine assembly for a three-strip Technicolor 35 mm movie camera. There are probably fewer than 300 of these on the planet. Things have changed so much that even the blue paint covering this camera part is not currently legal in California. One collector had actually rebuilt a complete three-strip camera. There are only about 15 working models today, out of a total of maybe 50 made. He knew Dr. Andreas, head of research at Technicolor, and was familiar with the dye collection donated to Eastman House. He said that some of these dyes were samples sent to Technicolor by dye manufacturing firms in the hopes of drumming up business.

The career of Technicolor Dye Transfer can be divided roughly into two periods: The first period, 1919 to 1952, Technicolor built and operated beam-splitting cameras which exposed separation negs on set. During the second period Technicolor mainly produced dye transfer release prints in 16 and 35 mm--although these included wide-screen formats such as Vista Vision and Cinerama.

During the initial period all of the films were two-color up until 1935 when the first live action, full color (three-strip), short "La Cucaracha" was released. An experimental two-color additive process film was produced in 1919, only a few frames of this survive and the additive process was discontinued. From then on the color in Technicolor films would depend on dyes which were generally available from commercial sources.

BEAM-SPLITTING CAMERAS

The design for these cameras evolved. Technicolor eventually created three different types. TYPE ONE CAMERA-- Layton and Pierce's book has excellent descriptions and photographs of the first type which is preserved at Eastman House. It was used to produce a black and white release print which ran two frames simultaneously. One frame was the record of the green light of the scene, and the other a record of the red-orange light. The green frame was projected through a green filter and the other through a red-orange filter. The two images were alined on top of each other and the separate light fields added up to a natural looking complete scene--an additive process. The camera used one strip of 35 mm film, panchromatic, which fed down on a vertical path, two frames at a time. Prisms and a semi-silvered mirror split the real image from the lens into two frames. The upper frame traveled through a red-orange gel filter, then to the film; the light from lower frame passed through a green filter. Only one feature film, "The Gulf Between" a silent, used this process.

TYPE TWO CAMERA-- Perhaps 10 of these cameras exist. Similar to the first type it has a vertical feed of a single strip of panchromatic 35 mm film, two frames at a time. Prisms and color filters present green and red-orange records in two separate frames; one of the frames is exposed upside down and next to its counterpart. The developed negative is then step-printed to prepare a green negative and a red-orange negative record. This camera design was used well into the talkie era.

TYPE THREE CAMERA-- The classic full color, three-strip, 35 mm camera; the machine that was used to photograph Errol Flynn's "Robin Hood", "The Wizard of Oz", "Gone With the Wind", "Singing In the Rain", "Shane" etc. A completely new lens was designed which provided more space behind the lens for the prism and semi-silvered mirror. The camera was loaded with three different rolls of black and white film--three strips. One roll preserved the record of the green light of the scene. This roll fed vertically one frame at a time directly behind the lens and through a green filter for exposure. The path of this light was straight and therefore this image had the best resolution. To render full color, though, a roll of film had also to capture a record of the blue light of the scene and another roll of film had to preserve a record of the red light. The prism/mirror system only provided for two image planes available to expose the rolls of film; one directly behind the lens for green light, and the other at a right angle to the first, for red light and blue light. So the red record and the blue record were exposed at the same place in the camera. To do this two pieces of film were fed into the exposure plane face-to-face: the light of the image passed through the front film--exposing it to blue light--and then continued to the back film, which was sensitive to red light. The front film preserved the blue record; the rear film, the red record. This configuration is called a "bi-pack" and was used in some form by many other color film systems. The light came from the lens. The semi-silvered mirror split part of it off and the prism sent it to the right. It passed through a filter that allowed only red and blue light to pass--this was magenta in color. The blue sensitive roll of film was orthochromatic, that is, sensitive only to blue and green light. Since the green light has been filtered out only the blue light exposed this roll. This roll of film also has a thinner plastic base so it will fit easily on top of the roll in the rear. Additionally, the back side of the blue roll was dyed red so that only red light would reach the rear roll of the bi-pack, which was meant to preserve only the red record of light. The red record roll of film was normal panchromatic stock. This design meant that the blue sensitive roll of film had to be custom manufactured. All three rolls of film were of the same length, one thousand feet, and were mounted side by side on top of the camera in a magazine.

Technicolor developed systems to quiet the sound of the camera, and for rear-screen projection effects. There were also cameras which worked at higher speed for slow-motion effects. The fire scene in "Gone With the Wind" was photographed in slow-motion.

PUTTING THE DYES INTO THE RELEASE PRINTS OF THE FILMS

Two methods were used to dye the release prints: 1) overlapping images cemented together on top of each other; and, 2) the imbibition or dye transfer process.

Layton and Pierce have a very good discussion of the "cement process". It was used only for two-color films and only in the silent era. A silver halide roll of film with an emulsion in unhardened gelatin was exposed through the base to all the green frames from the camera negative. The same was done with another roll of film for the red frames. The roll of film, which would become the release print, was developed in a hardening developer--pyrogallol--then immersed in a hot water bath. This etched off the gelatin which had no silver grains in it, but where the silver halide was developed the gelatin was hardened and would not dissolve in the hot water. Then the silver metal was bleached out of the roll with ferricyanide leaving a transparent gelatin relief image of the green frames in one roll and the red-orange frames in another roll. Then the green release print was floated on a tank full of green dye solution until it was properly colored. Next the red roll was floated on a solution of red-orange dye till it had the right color. Layton and Pierce even give the names of the particular dyes: for green, ACID GREEN and/or NAPTHOL GREEN; for red-orange, CROCEINE SCARLET and ORANGE A. Once properly dyed and dry the two rolls were glued onto each other in register, the red frames precisely overlapping the green frames. The cement used was an acetone and amyl alcohol mixture applied quickly. The sandwich of the two films was also subjected to pressure of as much as 200 pounds per square inch.

Unfortunately the cemented release prints were subject to delamination which would jam the projector. This encouraged Technicolor to develop method number two, the imbibition process.

DYE TRANSFER, IMBIBITION RELEASE PRINTS

Instead of using the dyed and hardened gelatin film to produce the final image which ran through the projector, Technicolor realized that the hardened gelatin strip--called a "matrix"--could transfer a dye image on a blank release print, that is, it could imbibe dye onto a fresh surface. After much research a machine was invented which could imbibe photographic dye images onto regular black and white release print stock producing imbibition prints. Briefly, here is the classic process:

A faint image from the green roll, frame lines and a soundtrack (when talkies started) were exposed on a normal roll of black and white Kodak release print stock. This release film was developed and fixed to yield a normal silver image, then it was bathed in a solution of chrome alum to harden it. The chrome alum made the gelatin harder but also served as a mordant for the dyes which were going to be transferred into the gelatin of the release print. (A mordant is a chemical which binds to a dye molecule and prevents it from smearing or washing out of the gelatin). The release print was now ready to absorb dyes, a procedure which should take place within twenty-four hours of the chrome alum bath.

The dye transfer theory was very simple. Dye solutions were prepared in either two different colors (green and red-orange for the two color process) or three different colors (yellow, a sky-blue called "cyan", and magenta for the full color process). Then a strip of film was developed which had an image of hardened gelatin that corresponded to the places where that color of dye would appear in the frame of the release print. This strip of film is called a matrix. So if the scene in the film was a shot of a sunflower then on the yellow matrix there would be a small layer of gelatin in the exact shape of the yellow petals of the flower. Since the petals are yellow only, there would be no gelatin in that location on the cyan matrix and the magenta matrix. The yellow matrix was dipped in a solution of yellow dye, rinsed off, and then pressed up against the release print. The gelatin image acted like a sponge for the yellow dye and this dye would flow out of the matrix and on to the correct locations in the release print. Other colors in the palette were made up of mixtures of the dyes. Since black requires all three dye colors, a shot of a black hat would generate a gelatin image of a hat on the yellow matrix, on the cyan matrix and on the magenta matrix. The yellow matrix was dipped in yellow dye, pressed against the release print, and a yellow dye image of the hat would transfer to the release print. Next, the cyan matrix was pressed against the release print, cyan dye would transfer exactly into the outline of the hat (this shape now looked dark green); and finally the magenta matrix was pressed against the release print and the magenta dye flowed on to it and turned the image of the hat completely black. Keeping the dyes precisely in the outlines of the shapes was a process called registration.

In a full color film three matrices had to be manufactured. To make the yellow matrix, the blue camera negative was printed onto raw matrix stock. This was developed in pyrogallol which hardened the gelatin around the image details. The unhardened gelatin was washed off in a hot water bath and the silver grains were bleached out with ferricyanide before the matrix was dipped in yellow dye. Similarly, to make the magenta matrix the green camera negative was printed on raw matrix stock, developed etc., etc.; for the cyan matrix, the red camera negative was printed on raw matrix stock, etc., etc.

THE DYE TRANSFER MACHINE

Anybody with any mechanical aptitude can see that this dye transfer process has a lot of places where it can go wrong. Technicolor developed an automatic machine that prevented these mistakes from happening. The release print and the matrix had to be kept in precise register during the whole time that the dye is flowing into the release print, a two minute long period. A stainless steel track about two inches wide and over two hundred feet long was formed into a loop and moved across a metal table. Along the sides of the track were pegs of silver coin metal which matched the sprocket holes of the release print and the matrix. First the release print was laid onto the track, emulsion side up, and its sprocket holes pressed over the pegs. Next ,as it moved along, a matrix full of fresh dye was pressed emulsion side down upon the release print. The two emulsions were in direct contact for two minutes with no air between them as the dye flowed into the release print. The the strips were pulled apart and the next matrix was fitted over the release print and a new color dye transferred during its two minute journey. Then finally a third matrix completed the full color film.

To prevent the dye from transferring before the matrix had been precisely fitted over the release print, a jet of cold water about 65 degrees f was sprayed on the matrix. This lowered the temperature below the transfer point and no dye would transfer until the matrix warmed up to about 100 degrees f. The water jet also eliminated any air between the two emulsions. The metal table contained pipes through which hot water flowed. As the pair of films were pulled by the peg track from the area where the matrix was first pressed on the release print the temperature of the table gradually got hotter until it reached as much as 130 degrees f. The film sandwich was kept at this temperature until the two minute process was finished and the matrix exhausted of all the dye it contained. The whole sequence was cyclical and once the exhausted matrix was peeled off the release print, the matrix traveled back to the dye tank and dipped into the dye solution again until it had received another full load of dye. Then it was pressed on a new release print and the cycle repeated.

To adjust the color intensity, after the matrix is dipped into the dye solution it is washed off by a jet of water containing sodium carbonate for as long as two minutes. For a darker color it is washed for a shorter time by this sodium carbonate solution. This is where we get the expression "color timing".

DYE RECIPES

Before 1952 Technicolor would create a custom mix of dyes for each particular film. The cyan color could contain as many as five different dyes; the yellow, three. Other substances were also added, for example oyster juice (this might have acted as a mordant). Apparently Technicolor still guards this information so it is very difficult to know which dyes were used for the initial release of a color film. Cornwell-Clyne lists one recipe with seven dyes. Friedman in "History of Color Photography" cites U.S. patents: for two color work see US 1807805; for three color, US 1900140.

Dr. Richard Goldberg joined Technicolor in 1952 and he redesigned the dyes and mordants for the dye transfer process. He invented formulas for dyes which required only one dye for each of the colors yellow, cyan and magenta. These were manufactured by the American Cyanamide Company and also seem to be propriatory. Since Dr. Goldberg helped set up the Technicolor exhibit at Eastman House I believe everyone should respect his rights and let these chemicals remain secret. Some information is in the public domain from US patents, see US 3625694 and US 2583076.

"The Dawn of Technicolor" is a thorough account of the beginnings of the company and the films it made using the earliest processes up until the first full color camera. It deals minutely with business decisions and provides clear biographical details of the people involved at the center of the firm. These are some of the most important names in the history of color photography: Kalmus, E.J. Wall, Comstock, Troland et al. The editors provide beautiful color reproductions of frames and images from all of the major films in the period they discuss; to which they add a complete filmography which lists all of the holdings for these films in principal institutions worldwide. The book however does shy away from specific technical descriptions. It only mentions two specific dyes; does not describe mordants, formulas, temperature or timing. For this information you must look to Cornwell-Clyne or relevant patents.

Out here in greater Los Angeles where movies are a religion I go to a collectors' group where vintage film prints are shown. A couple of months ago one of the collectors brought in a magazine assembly for a three-strip Technicolor 35 mm movie camera. There are probably fewer than 300 of these on the planet. Things have changed so much that even the blue paint covering this camera part is not currently legal in California. One collector had actually rebuilt a complete three-strip camera. There are only about 15 working models today, out of a total of maybe 50 made. He knew Dr. Andreas, head of research at Technicolor, and was familiar with the dye collection donated to Eastman House. He said that some of these dyes were samples sent to Technicolor by dye manufacturing firms in the hopes of drumming up business.

The career of Technicolor Dye Transfer can be divided roughly into two periods: The first period, 1919 to 1952, Technicolor built and operated beam-splitting cameras which exposed separation negs on set. During the second period Technicolor mainly produced dye transfer release prints in 16 and 35 mm--although these included wide-screen formats such as Vista Vision and Cinerama.

During the initial period all of the films were two-color up until 1935 when the first live action, full color (three-strip), short "La Cucaracha" was released. An experimental two-color additive process film was produced in 1919, only a few frames of this survive and the additive process was discontinued. From then on the color in Technicolor films would depend on dyes which were generally available from commercial sources.

BEAM-SPLITTING CAMERAS

The design for these cameras evolved. Technicolor eventually created three different types. TYPE ONE CAMERA-- Layton and Pierce's book has excellent descriptions and photographs of the first type which is preserved at Eastman House. It was used to produce a black and white release print which ran two frames simultaneously. One frame was the record of the green light of the scene, and the other a record of the red-orange light. The green frame was projected through a green filter and the other through a red-orange filter. The two images were alined on top of each other and the separate light fields added up to a natural looking complete scene--an additive process. The camera used one strip of 35 mm film, panchromatic, which fed down on a vertical path, two frames at a time. Prisms and a semi-silvered mirror split the real image from the lens into two frames. The upper frame traveled through a red-orange gel filter, then to the film; the light from lower frame passed through a green filter. Only one feature film, "The Gulf Between" a silent, used this process.

TYPE TWO CAMERA-- Perhaps 10 of these cameras exist. Similar to the first type it has a vertical feed of a single strip of panchromatic 35 mm film, two frames at a time. Prisms and color filters present green and red-orange records in two separate frames; one of the frames is exposed upside down and next to its counterpart. The developed negative is then step-printed to prepare a green negative and a red-orange negative record. This camera design was used well into the talkie era.

TYPE THREE CAMERA-- The classic full color, three-strip, 35 mm camera; the machine that was used to photograph Errol Flynn's "Robin Hood", "The Wizard of Oz", "Gone With the Wind", "Singing In the Rain", "Shane" etc. A completely new lens was designed which provided more space behind the lens for the prism and semi-silvered mirror. The camera was loaded with three different rolls of black and white film--three strips. One roll preserved the record of the green light of the scene. This roll fed vertically one frame at a time directly behind the lens and through a green filter for exposure. The path of this light was straight and therefore this image had the best resolution. To render full color, though, a roll of film had also to capture a record of the blue light of the scene and another roll of film had to preserve a record of the red light. The prism/mirror system only provided for two image planes available to expose the rolls of film; one directly behind the lens for green light, and the other at a right angle to the first, for red light and blue light. So the red record and the blue record were exposed at the same place in the camera. To do this two pieces of film were fed into the exposure plane face-to-face: the light of the image passed through the front film--exposing it to blue light--and then continued to the back film, which was sensitive to red light. The front film preserved the blue record; the rear film, the red record. This configuration is called a "bi-pack" and was used in some form by many other color film systems. The light came from the lens. The semi-silvered mirror split part of it off and the prism sent it to the right. It passed through a filter that allowed only red and blue light to pass--this was magenta in color. The blue sensitive roll of film was orthochromatic, that is, sensitive only to blue and green light. Since the green light has been filtered out only the blue light exposed this roll. This roll of film also has a thinner plastic base so it will fit easily on top of the roll in the rear. Additionally, the back side of the blue roll was dyed red so that only red light would reach the rear roll of the bi-pack, which was meant to preserve only the red record of light. The red record roll of film was normal panchromatic stock. This design meant that the blue sensitive roll of film had to be custom manufactured. All three rolls of film were of the same length, one thousand feet, and were mounted side by side on top of the camera in a magazine.

Technicolor developed systems to quiet the sound of the camera, and for rear-screen projection effects. There were also cameras which worked at higher speed for slow-motion effects. The fire scene in "Gone With the Wind" was photographed in slow-motion.

PUTTING THE DYES INTO THE RELEASE PRINTS OF THE FILMS

Two methods were used to dye the release prints: 1) overlapping images cemented together on top of each other; and, 2) the imbibition or dye transfer process.

Layton and Pierce have a very good discussion of the "cement process". It was used only for two-color films and only in the silent era. A silver halide roll of film with an emulsion in unhardened gelatin was exposed through the base to all the green frames from the camera negative. The same was done with another roll of film for the red frames. The roll of film, which would become the release print, was developed in a hardening developer--pyrogallol--then immersed in a hot water bath. This etched off the gelatin which had no silver grains in it, but where the silver halide was developed the gelatin was hardened and would not dissolve in the hot water. Then the silver metal was bleached out of the roll with ferricyanide leaving a transparent gelatin relief image of the green frames in one roll and the red-orange frames in another roll. Then the green release print was floated on a tank full of green dye solution until it was properly colored. Next the red roll was floated on a solution of red-orange dye till it had the right color. Layton and Pierce even give the names of the particular dyes: for green, ACID GREEN and/or NAPTHOL GREEN; for red-orange, CROCEINE SCARLET and ORANGE A. Once properly dyed and dry the two rolls were glued onto each other in register, the red frames precisely overlapping the green frames. The cement used was an acetone and amyl alcohol mixture applied quickly. The sandwich of the two films was also subjected to pressure of as much as 200 pounds per square inch.

Unfortunately the cemented release prints were subject to delamination which would jam the projector. This encouraged Technicolor to develop method number two, the imbibition process.

DYE TRANSFER, IMBIBITION RELEASE PRINTS

Instead of using the dyed and hardened gelatin film to produce the final image which ran through the projector, Technicolor realized that the hardened gelatin strip--called a "matrix"--could transfer a dye image on a blank release print, that is, it could imbibe dye onto a fresh surface. After much research a machine was invented which could imbibe photographic dye images onto regular black and white release print stock producing imbibition prints. Briefly, here is the classic process:

A faint image from the green roll, frame lines and a soundtrack (when talkies started) were exposed on a normal roll of black and white Kodak release print stock. This release film was developed and fixed to yield a normal silver image, then it was bathed in a solution of chrome alum to harden it. The chrome alum made the gelatin harder but also served as a mordant for the dyes which were going to be transferred into the gelatin of the release print. (A mordant is a chemical which binds to a dye molecule and prevents it from smearing or washing out of the gelatin). The release print was now ready to absorb dyes, a procedure which should take place within twenty-four hours of the chrome alum bath.

The dye transfer theory was very simple. Dye solutions were prepared in either two different colors (green and red-orange for the two color process) or three different colors (yellow, a sky-blue called "cyan", and magenta for the full color process). Then a strip of film was developed which had an image of hardened gelatin that corresponded to the places where that color of dye would appear in the frame of the release print. This strip of film is called a matrix. So if the scene in the film was a shot of a sunflower then on the yellow matrix there would be a small layer of gelatin in the exact shape of the yellow petals of the flower. Since the petals are yellow only, there would be no gelatin in that location on the cyan matrix and the magenta matrix. The yellow matrix was dipped in a solution of yellow dye, rinsed off, and then pressed up against the release print. The gelatin image acted like a sponge for the yellow dye and this dye would flow out of the matrix and on to the correct locations in the release print. Other colors in the palette were made up of mixtures of the dyes. Since black requires all three dye colors, a shot of a black hat would generate a gelatin image of a hat on the yellow matrix, on the cyan matrix and on the magenta matrix. The yellow matrix was dipped in yellow dye, pressed against the release print, and a yellow dye image of the hat would transfer to the release print. Next, the cyan matrix was pressed against the release print, cyan dye would transfer exactly into the outline of the hat (this shape now looked dark green); and finally the magenta matrix was pressed against the release print and the magenta dye flowed on to it and turned the image of the hat completely black. Keeping the dyes precisely in the outlines of the shapes was a process called registration.

In a full color film three matrices had to be manufactured. To make the yellow matrix, the blue camera negative was printed onto raw matrix stock. This was developed in pyrogallol which hardened the gelatin around the image details. The unhardened gelatin was washed off in a hot water bath and the silver grains were bleached out with ferricyanide before the matrix was dipped in yellow dye. Similarly, to make the magenta matrix the green camera negative was printed on raw matrix stock, developed etc., etc.; for the cyan matrix, the red camera negative was printed on raw matrix stock, etc., etc.

THE DYE TRANSFER MACHINE

Anybody with any mechanical aptitude can see that this dye transfer process has a lot of places where it can go wrong. Technicolor developed an automatic machine that prevented these mistakes from happening. The release print and the matrix had to be kept in precise register during the whole time that the dye is flowing into the release print, a two minute long period. A stainless steel track about two inches wide and over two hundred feet long was formed into a loop and moved across a metal table. Along the sides of the track were pegs of silver coin metal which matched the sprocket holes of the release print and the matrix. First the release print was laid onto the track, emulsion side up, and its sprocket holes pressed over the pegs. Next ,as it moved along, a matrix full of fresh dye was pressed emulsion side down upon the release print. The two emulsions were in direct contact for two minutes with no air between them as the dye flowed into the release print. The the strips were pulled apart and the next matrix was fitted over the release print and a new color dye transferred during its two minute journey. Then finally a third matrix completed the full color film.

To prevent the dye from transferring before the matrix had been precisely fitted over the release print, a jet of cold water about 65 degrees f was sprayed on the matrix. This lowered the temperature below the transfer point and no dye would transfer until the matrix warmed up to about 100 degrees f. The water jet also eliminated any air between the two emulsions. The metal table contained pipes through which hot water flowed. As the pair of films were pulled by the peg track from the area where the matrix was first pressed on the release print the temperature of the table gradually got hotter until it reached as much as 130 degrees f. The film sandwich was kept at this temperature until the two minute process was finished and the matrix exhausted of all the dye it contained. The whole sequence was cyclical and once the exhausted matrix was peeled off the release print, the matrix traveled back to the dye tank and dipped into the dye solution again until it had received another full load of dye. Then it was pressed on a new release print and the cycle repeated.

To adjust the color intensity, after the matrix is dipped into the dye solution it is washed off by a jet of water containing sodium carbonate for as long as two minutes. For a darker color it is washed for a shorter time by this sodium carbonate solution. This is where we get the expression "color timing".

DYE RECIPES

Before 1952 Technicolor would create a custom mix of dyes for each particular film. The cyan color could contain as many as five different dyes; the yellow, three. Other substances were also added, for example oyster juice (this might have acted as a mordant). Apparently Technicolor still guards this information so it is very difficult to know which dyes were used for the initial release of a color film. Cornwell-Clyne lists one recipe with seven dyes. Friedman in "History of Color Photography" cites U.S. patents: for two color work see US 1807805; for three color, US 1900140.

Dr. Richard Goldberg joined Technicolor in 1952 and he redesigned the dyes and mordants for the dye transfer process. He invented formulas for dyes which required only one dye for each of the colors yellow, cyan and magenta. These were manufactured by the American Cyanamide Company and also seem to be propriatory. Since Dr. Goldberg helped set up the Technicolor exhibit at Eastman House I believe everyone should respect his rights and let these chemicals remain secret. Some information is in the public domain from US patents, see US 3625694 and US 2583076.

Attachments

Last edited by a moderator: