Sorry this kinda stuff confuses the hell outta me

Hi, in my view these things are hard to understand unless you can kinda grasp the principles behind them. The manufacturer's instructions generally give step-by-step instructions; they pretty much have to do it this way. But it doesn't help one understand the "whys" behind everything.

Let me try to explain the principles; this is gonna get kinda wordy. But if you can follow things you will hopefully get a grasp of whats going on.

I was first exposed to these concepts as a young photolab QC tech in the 1970s. One of our duties was to refill processing machines after overhauls been completed. Although I had quite a lot (I thought) of photo experience by then it was still confusing. The senior tech explained it to me thusly: he said, Don't think of it as "developer." Think of it as either "tank solution" or "replenisher." Where the so-called "tank solution," or as koraks said, "tank mix," is what most photographers would refer to as simply "developer." (In photo labs we use the term "tank" in reference to processing machine tanks, thus the so-called tank solution. )

Here's how it sorta works. The developer "tank solution," aka just "developer" to non-lab people, is where the film or paper is actually developed. During development two main things happen to the developer. First is that a certain amount of developing agent is "used up," depending on the extent of "developing" that has to be done. (Unexposed film frames, for example, will not exhaust the developer as no silver is developed. Whereas completely light-fogged film will exhaust the developer much more strongly than "normal" exposures.) The second thing happening to the developer is that development byproducts are being released into it. Typically these byproducts will slow down the development significantly. But... in the specific case of RA-4 paper, this effect is fairly minor.

So... the way that this developer exhaustion is traditionally dealt with in the photo processing business is through the use of so-called replenishers. Such replenishers are (ideally) formulated to exactly counteract the bad effects of developer exhaustion. The developer replenisher does mainly two things. First, it restores the tank-solution developing-agent concentration back to the original aim specification. (To do this replenisher must be overly concentrated with respect to the actual developing-agent.) Second, the replenisher volume must be high enough to dilute the unwanted byproducts back to the original aim specification.

As a note, the manufacturers typically offer developer replenishers designed for different replenishment rates. If you compare high-rate vs low-rate replenishers, the low-rate replenisher will necessarily a higher concentration of the developing agent. At the same time the low-rate replenisher will contain a lower concentration (perhaps zero) of "byproducts." But in either case the replenisher will be significantly "stronger," in developing action, than the standard "tank solution," so the replenisher is not suitable, as is, for use in developing film or paper.

Now for the topic of "starter solutions." You might wonder, what is the point of these? Well, in the photo processing business labs typically do not expect to have to refill their processing machines on any regular basis - a commercial replenished system can run indefinitely. Certainly for years and years, using machines with filtered circulation systems and being "monitored" by qualified technicians who can adjust the replenishment rates as needed. So the typical photo lab will only purchase and stock replenisher packages.

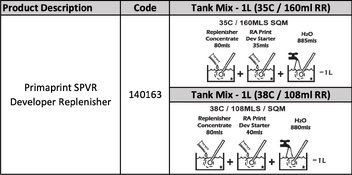

But occasionally they will screw up and have to fill a processing machine with freshly mixed "developer" (tank solution.) So the question is, how can they do this when all they have are replenisher mixes? Well, the manufacturers have accommodated this by also manufacturing the so called starter solutions along with specific instructions for their replenishers. In essence these allow photo labs to convert developer "replenisher" into developer "tank solution." In essence this conversion does two things. First, since the replenisher has an extra-high concentration of the developing-agent it needs to be somewhat diluted with water. And this will vary with the design replenishment-rate of the specific replenisher so one has to follow the instructions specific to their replenisher. The second thing is that the replenisher is at least somewhat deficient in "development byproducts," so these are supplied in the starter solution. (As I mentioned before, in the specific case of the RA-4 process, it is not very sensitive to said byproducts, so not as important as, for example, as in the C-41 film process. ) The starter solution can contain some other things, but the main things are as mentioned above.

A couple of notes related to replenished systems in general. When you see published replenishment rates these are based on an "average" amount of exposure. Ideally you would have a way to keep track of the developer's "activity" and make periodic adjustments to the replenishment rate as needed. But... RA-4 is especially forgiving in this respect, so... ? But if you were to make a lot of prints with nearly black backgrounds, this might require something like 3 to 4 times the "normal" replenishment rate. So just something to be aware of.

Second note: color developers, in general, have pretty small amounts of "preservatives" compared to typical b&w developers. (The preservatives help protect the developing-agent from oxidation.) So if your processing method aerates the developer to a significant degree it might not be suitable for a replenished system. My color experience is all in commercial-type systems; I don't have much idea how far one can push things when aeration becomes significant. I would defer to the actual experience of others here.