I think I mentioned I was once able to inspect prints of Demachy in the original, and though this is several years back, I vividly remember their subtle tonality. On the back of one print, I recall, a curator had noted that Demachy here was still learning, as there were some blown-out highlights and empty shadows.

I really don't want to endulge in ancestor-worship, but I think it would be very worthwhile to trace the negativs and compare them with the prints in order to learn more about Demachy's printing methods. I also cannot help thinking that his paper, for instance, must have been quite different from today's quality, and I recall him writing somewhere that gelatine sizing is detrimental to gum - a remark I find mystifying.

I think Katharine is right in her suggestion that he used lamp black for his black pictures, probably mixed with some other pigments to vary tonality.

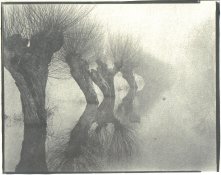

I attach an effort of mine of a single-run gum print in, if I am not very mistaken, bone-black hwich I just scanned in. I hope densities may be more or less recognized.

Lukas, you have the advantage of me in having seen Demachy's prints in person; I can only go by the reproductions I have at hand (in my bookcase and on the web), by remarks of curators and of critics both at the time and more recently, and by the publication "Photo-Aquatint, or the Gum-Bichromate Process" a detailed explanation of the process and description of his methods, written with Alfred Maskell, for the impressions I draw of his work.

Commentators, both past and present, are unanimous in their judgment that he often engaged in heavy retouching of the negative (by painting out areas that he deemed distracting and emphasizing other areas) as well as heavy post-exposure manipulation, and his own writing certainly confirms that impression. He held the idea that a straight photographic print was just a mechanical reproduction of reality, therefore not "art" and in order to make a photograph a work of art, one needed to employ considerable handwork. "Meddling with a gum print may or not add the vital spark; without the meddling, there can be no spark," he wrote. Crawford's summary of Demachy's work: "Demachy was most interested in the painterly and gestural qualities the [gum] process made possible. His prints often made a considerable show of brush strokes, and the tonal scale, instead of having a continuous progression of tones, often jumps in patches from light to dark." Several commentators' descriptions mention his adding white pastel to bring out highlghts in the print.

As I mentioned the other day, I have seen reproductions of some prints that have a subtlety of tone, such as the one of the back of the girl's head done in Venetian red that everyone knows (also a couple of nudes with very delicate tonality) but these don't seem remarkable to me as one-coat gums. Nice, but hardly beyond the reach of any competent modern worker who understands that subtlety of tonality is largely a function of pigmentation.

But as far as the progression of his work over time, the curator's note Lukas mentioned on the back of the print makes no sense to me in the context of the reproductions I've seen. That print in red, showing the woman to have a full head of hair and giving a very nice gradation in the filmy cloud of gauze around her shoulders, is given a date of 1898 in Camera Notes; another print of apparently the same subject with the same hairdo but a different pose, that has the highlights so blown out that it looks like she has a big bald patch on the side of her head, is given the date of 1900. (And it looks that way in a variety of different reproductions, so it's not just one particular reproduction that didn't reflect the print accurately). So I'm not sure that his work could be seen as a progression in the direction of printing a full photographic tonal scale. And while some of the published heavily-pigmented and gritty works (essentially one dark tone, with lighter tones obviously carved out of the darkness with forced development) were dated before 1898, many of the darkest ones with the least tonal gradation were dated between 1902 and 1906 (that's the latest date of any of the reproductions I've seen).

Contemporary photographers who were determined to make artistic photographs by using only the controls and methods inherent to photography rather than borrowing the methods and aesthetics of painting (notably P.H. Emerson) were openly contemptuous of Demachy's work. In answer to one criticism that his prints resembled painting more than photography, he answered that it wasn't like painting at all; while painters use the brush to apply pigment to the surface, he merely uses the brush to remove pigment to reveal the image the camera recorded. Which seems rather an artificial distinction to me, but ... whatever. The point is that from his own remarks and the remarks of observers, as well as from my own observations of (admittedly reproductions of) his work, I'm not led to a conclusion that Demachy's overall goal was to produce in gum a print that reproduced the continuous full-scale tonality of a traditional photograph, although he did do that occasionally, within gum's short-scale limitations.

About the gelatin sizing, I'm perplexed; I didn't know he had ever said that. From the Maskell-Demachy instructions for the gum process: "Some papers may require sizing, though, as a rule, one may be reasonably content with those which ...already possess the desired surface. Should it be necessary to do so, it is easy to size with either gelatine or arrowroot."

I don't "suppose" that he used lamp black for his black prints; I took that directly from the "pigments or colours" section of the "Materials used in the process" section of that same paper. He does mention that it is also possible to use India ink, but adds that it requires very careful grinding and mixing, and concludes that "lampblack, added to ochers and umbers and indigo, will form, separately or combined, a palette with which ...we may be very well satisfied."

Interesting discussion,

Katharine