what would be the benefit of a slow asa, other than really longer exposure times?

Would fine grain be that much finer?

Longer exposure times are an advantage if you don't have a shutter for the lens, for example if exposing by removing the lens cap, a Neutral Density filter does the same than having a lower density.

With the

same technology if ISO is lowered to 1/4 then typical grain diameters decrease to the half. Grain sensitivity is proportional to the grain surface taking light, area is proportional to diameter, so if crystals used have x2 diameter then sensitivity increases x4.

You cannot compare films sporting different technology... T-Max and Delta (and Neopan) have flat grains delivering an smaller than expected grain size, compared to cubic crystals, the same surface exposed to light contains less silver halide.

Also during Emulsion Sensitization, etc speed can be boosted more or less. So in general, with the same film type, you can enlarge, compared to ISO 100, you can enlarge x2 a ISO 25 shot, having a similar grain size in the print. Still many factors are there like developer or condenser vs diffuser enlargers.

Also with low ISO films you can expect a lower highlight latitude. Usually very small crystals are also present in high speed film, you overexpose those less if using a high ISO exposure, so they are more difficult to saturate.

With high acutance developer, would this be overkill on the resolution ?

Acutance and resolution are different concepts, sharpness is (mostly) the combination of resolving power with acutance.

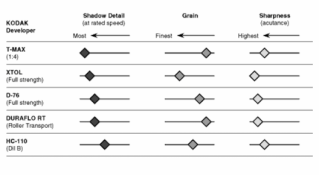

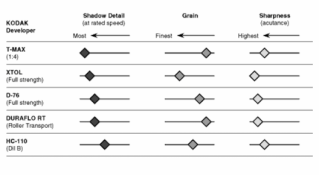

If you want great acutance easy then I'd use Xtol, developing in tray with reduced agitation. Acutance is a bit improved (seen only in very large prints for the format) from edge effects obtained from low agitation.

See The Darkroom Cookbook:

https://silveronplastic.files.wordp...ookbook-3rd-ed-s-anchell-elsevier-2008-ww.pdf

When you can, just purchase the new The Film Development Cookbook, to support the authors and to get an extensive masterliness about that.

With high acutance developer, would this be overkill on the resolution ?

I have seen some outstanding 4x5 work with Tmax 100 at higher emulsion speed.

Not the lens, not the film, not the developer... what is sharp or not it's the photographer himself.

Your technique it's what will deliver the kind of shot you want. Acutance of the is related a lot with illumination. Illumination it's very complex you have diffuse and directional components, and this have interaction with textures.

Of course film, developer and processing have an impact, but this is only a 1/10 of the tale. Focus, DOF, Aperture, Vibrations, Subject, illumination are (say) another 1/10. The remaining 80% is the photographer's capability to optimize all that to get the sharpness (more or less) he wants for the shot.

Let me recommend you this book you can get used nearly for free:

Lastly, even when reading technical details on Ansel Adams or Avedon they seemed to favor super-x?

Or tri x in later years and still got great sharpness and detail....with higher Asa/iso films.

FLEXIBLE vs EASY TO PRINT

Super-X was IMO a more linear film, compared. Perhaps, at some point, Adams saw that having a flexible negative could be benefical in some situations, and for sure his disciple John Sexton was very influential at Kodak in the T-Max linear capture way. In that era (early 1980s) it happened that Variable Contrast paper became a sound choice, it existed since 1940's but it was in early 1980's that it became a sound choice from product improvement. Since then we burn highlights in 00 grade and shadows in 5 grade, making a linear capture more suitable because involved greater image manipulation ends less in botched job (for challenging scenes). Graded paper can be suitable but VC has that principal advantage: we dodge/burn with different grades, this is not possible with graded papers.

If you are scan/hybrid then a linear film is perfect, no problem...

If you are to make sound prints in the darkroom then you have two choices (and anything in the middle) if the scene range surpasses the paper dynamic range and you have to compress shadows or highlights to fit...

1) Using a film/processing combination that compresses shadows/highlights (totally or partially) in a way the negative it's easy to print, you have to control well exposure and knowing a lot how the thing works. An example is Yousuf Karsk ultramaster portraiture, he used toe a lot to get the shadow depiction controlled, and shadows can be very important in portraits... Also Zone System is mostly based using compressed and linear zones, making usage from toe/shoulder

2) Taking a very linear capture with a very linear film/processing, this yields a very flexible negative that it may be quite diffcult to print, requiring extensive image manipulation (dodging/burning) or advanced (time consuming) masking like SCIM, HLM, etc. Other ways to get highlight texture with linear films (and high DR scenes) is using pyro developers as the stain blocks more the blue so the higher proportional stain in the highlights lowers the effective contrast there, compressing the highlights, another way is long toe (to print the negative shoulder) silver chloride paper: Lodima, Lupex or the killed Kodak AZO, but this is more suitable for contact copies because it's low speed, still with LED boosted enlargers this can be overcomed.

But if you scan then you blend the curves like you want in Photoshop, no problem if scanning/editing 16 bits per channel (save in TIFF to preserve the 16 bits). Problem is if one gets used to scan only then the negatives can be difficult to print optically and as we have no feedback then we don't refine the negative crafting for the darkroom way.